|

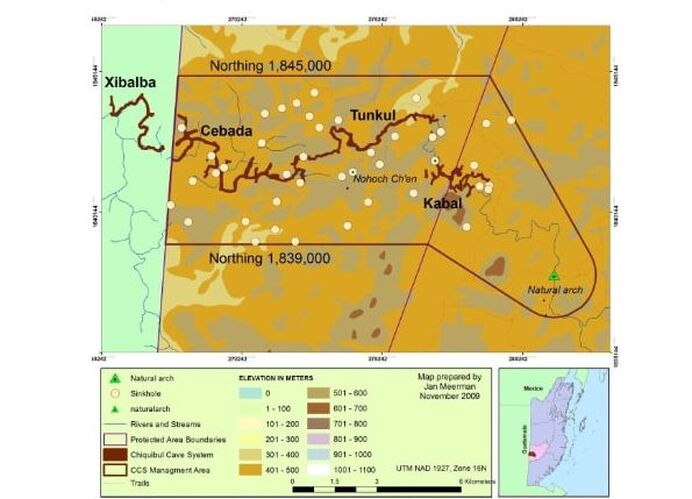

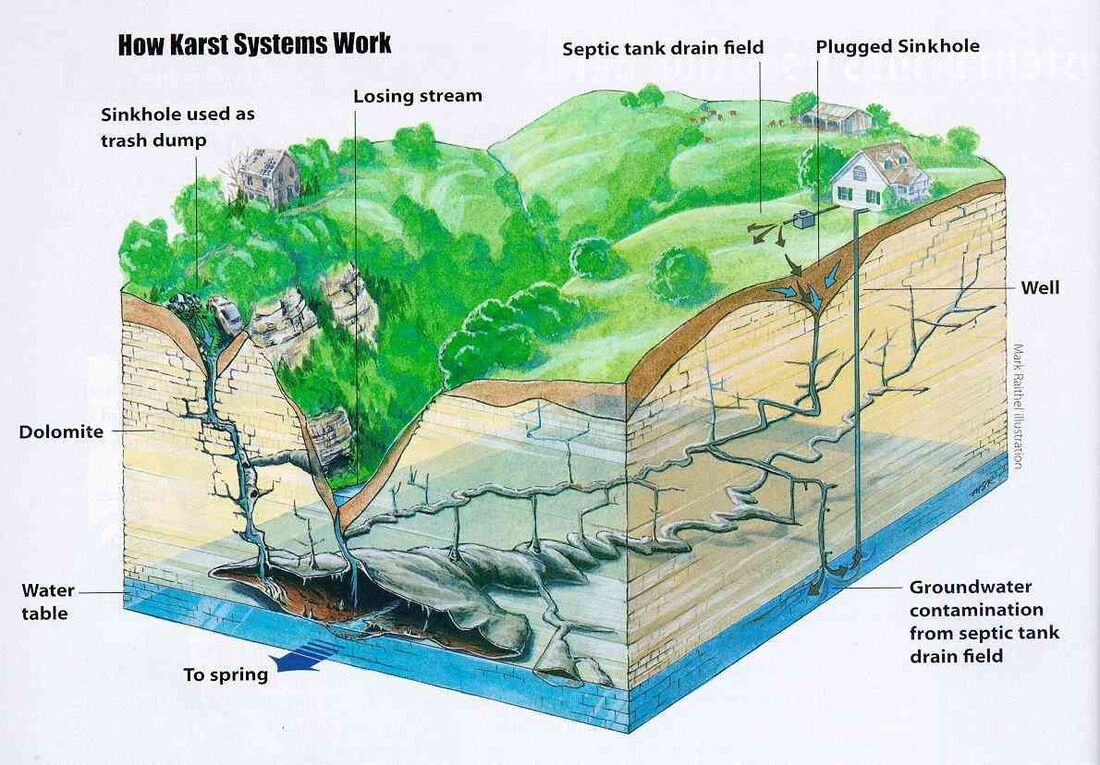

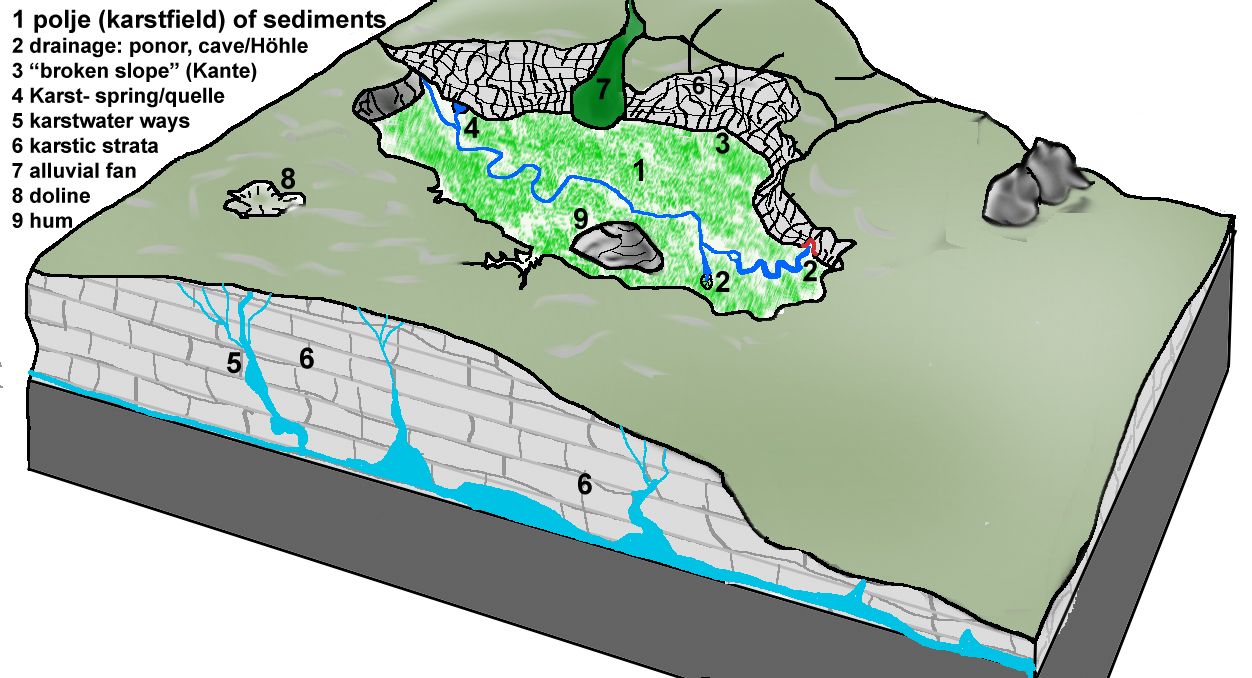

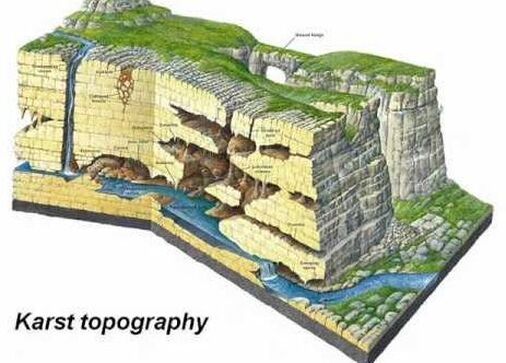

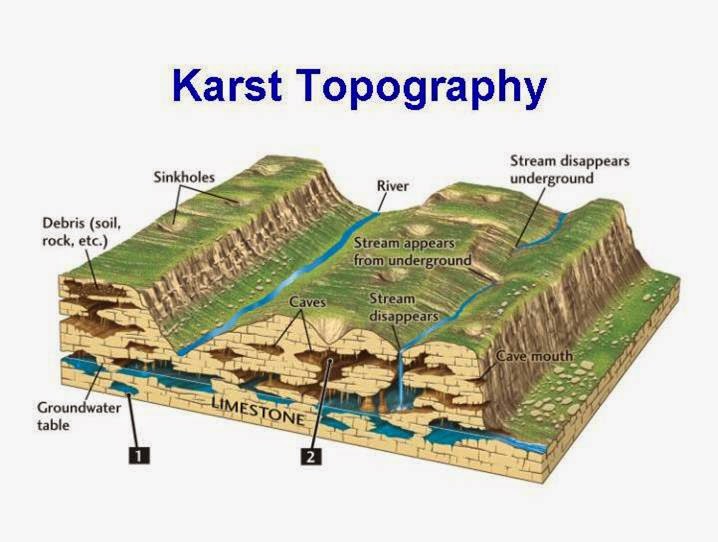

Nohoch Ch'en Sinkhole Nestled deep within the Chiquibul National Park lies a series of massive sinkholes. The Nohoch Ch'en Sinkhole, largest of which is nearly 1,000 feet wide and 600 feet deep, is about the same size as the famous Blue Hole (located at Lighthouse Reef Atoll). This sinkhole lies in a massive karst environment (which consists of about 40 other sinkholes). A karst environment exists when there is a series of underground caves which begin to collapse, losing their roof and creating a sinkholes. This karst environment is home to many unique features. Nohoch Ch'en the largest sinkhole in the area, is unique in the fact that there is only one small bridge of jungle connecting the jungle at the bottom of the sinkhole to the surrounding jungle, meaning it is a relatively isolated habitat. Within the sinkhole, team members found many species of reptiles and amphibians, rare ferns and orchids, and a possibly nesting pair of the incredibly rare Orange Breasted Falcon. Perhaps one of the most breathtaking discoveries was the remaining evidence of the significance of this sinkhole to the Ancient Maya. Within and surrounding the sinkhole, many structures, plazas, pottery, and other evidence was commonplace. Inside the sinkhole itself, many artifacts were found including 4 unbroken pots high up the cliff face in a small cave. Nohoch Ch'en is but one of many amazing features of the Chiquibul, but it is not without it's threats. Deforestation and incursions from over the border threaten this beautiful land, and it is up to the govering rangers of FCD (Friends of Conservation & Development), and all of us to protect it. The Red Line shows the Chiquibul Cave System (Going from Kabal Cave (in Belize) & extending to the XIbalba Cave (in Guatemala) The yellow dots, represent all the sinkholes in the area. You can see the location of the Nohoch Ch'en Sinkhole. CHIQUIBUL CAVE SYSTEM CHIQUIBUL CAVE SYSTEM Each year, rain falls on the non-carbonate rocks of Belize’s Maya Mountains and flows west toward the karstic Vaca Plateau. The Chiquibul River goes underground connecting the Chiquibul System’s Kabal Cave Group, which connects (4) caves, by one waterway passage (the Chiquibul River). The cave system consists of four big caves and numerous sinkholes, which have been extensively explored during the last 30 years. Actun Kabal (Kabal Group) - This upper section of the Chiquibul Cave System has over 12 km of mapped passages, with a depth of -95 m. Included is Chiquibul Chamber, at 250 m by 150 m one of the world's largest caverns. 1. Actun Kabal Cave - The upper end of Kabal Cave System Group there is ponded waters with large, washed-in rotting trees and organic debris. Downstream the system holds less water and organic material because fewer collapses intersect the cave. Passages in the cave are generally 10-60 m wide and 10-30 m high. The downstream end of the Kabal Cave System Group is a valley collapsed passage that ends at the entrance of the Actun Tunkul. 2. Actun Tunkul Cave (Stone Drum) - Includes Belize chamber with dimensions of 300m by 150m by 65m, it is one of the largest natural caverns in the world. TunKul was connected with Cebada cave in 1999, resulting in a 39m long cave. Most of the floor is a thick deposit of sand and silt laden with organic debris. The cave ends in a deep sump about 500 m from the upstream end of Cebada cave. 3. Cebada Cave - Cebada Cave and Tun Kul were linked in 1999; at 39 km it is the longest cave in Belize. The entrance to Cebada Cave is 1.5 km east of the Guatemalan border at the base of a deep collapsed sinkhole, like the other caves of the Chiquibul System. The passage is similar to Actun Tunkul but has more side passages and the side passages tend to be longer. Downstream from the Cebada entrance, the Chiquibul River flows about 2.2 km and sumps just before reaching Guatemala. 4. Xibalba Cave (Guatemala) - This downstream section of the Chiquibul Cave System is entirely within Guatemala, and is the country's deepest cave. Over seven kilometres of passages have been mapped, including some that are over 100 m wide. The cave entrance is 200 m across. The river discharges below Xibalba’s main entrance, with (2) other significant passages also occur in this cave. (Passage #1) Is a dry (upper level, 30-m-wide by 20-m-high) passage that extends north from the main entrance. (Passage #2) Begins at the Zactun sinkhole and extends as a series of lakes for nearly 3 km to the upstream end of the main passage. Exploring the Chiquibul Kabal Cave System Cavers Mike Boon and Tom Miller visited the area in 1971 and 1982 respectively, with Miller initiating the first cave explorations. Miller followed up with major international expeditions in 1984, 1986 and 1988, partially funded by National Geographic and the National Speleological Society. First expedition - surveyed the dry cave passages in Kabal and Tun Kul at the upstream part of the system, ending at a sump at the end of Tun Kul. Second expedition - surveyed dry cave passages and river passages in Cebada and Xibalba. Third expedition - attempted but failed to connect Cebada with Tun Kul. In 1990 a comprehensive cave survey was prepared by Steve Grundy and Olivia Whitwell. Thousands of years ago, most of the landmass of Belize was covered by a broad, shallow tropical sea. One of the major rock types deposited in this sea was limestone, a rock formed of calcium carbonate. This limestone can have its origin either from biological materials like corals and mollusks, or in some cases the limestone can be precipitated directly from the seawater. Geology of the Belize Caves System Like the modern Gulf of Mexico, this shallow Cretaceous sea was occasionally subject to violent storms that disturbed the floor of the sea. These storms created a distinctive type of limestone rock called a breccia. Breccia is a rock that is made up of angular pieces of other rocks. The angular pieces of rock are called “rip up clasts.” These are pieces of rock several inches on a side that were torn up and jumbled about before the clasts or pieces had a chance to harden. The distinctive rock is very easy to dissolve. Almost all limestone is soluble in a dilute solution of carbonic acid. Thousands of years later, these Cretaceous limestone formations were uplifted on the northern flanks of the Maya Mountains. After these mountains were uplifted, water would run off the crystalline rocks, and come into the outcrop of the Cretaceous limestone. As the rainwater fell through the atmosphere, it would react with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. After the rain fell into the soil on the crest of the Maya Mountains, the water would absorb additional carbon dioxide from decaying plant material. The rainwater turns into a weak acid, which then reacts with the limestone rock. The acidic rainwater enters the limestone rock, and travels along zones of weakness called joints. Joints are microscopic cracks in the rock that are produced by mountain building processes (tectonics) and by earth tides (similar to oceanic tides). Water finds it easier to dissolve into the limestone than to flow across the limestone outcrop, creating a karst landscape. Nohoch Ch'em Sinkhole, as it sits in a karst landscape. Karst Landscape - This process of solution produces a distinctive type of landscape characterized by caves, sinkholes, and a lack of surface drainage. This landscape is called a Karst landscape, named for a region in former Yugoslavia. These processes of solution are accelerated in a tropical climate, so Belize is an example of a tropical Karst environment. The karst landscapes evolve though various stages which can be called (1) Youth Stage, (2) Middle Age Stage, and (3) Old Age Stage. The Cave Branch area, is part of the Old Age Karst landscape. One of the distinctive features of an old age landscape is a feature called a Karst window. Karst Wndows - As caves come to intersect with the land surface, they begin to collapse. This means that caves gradually lose their roofs. An underground river like the Sibun or Caves Branch River will run intermittently through the caves and above ground. Eventually, the caves will completely collapse, and the caves will be replaced by a valley without a roof. Karst Window - In A Old Age Stage - Kartst Landscaping This is similar to what you find in the Chiquibuil As the caves collapse and are destroyed by erosion, a single cave that was once very large (or long), becomes divided into a series of shorter caves. Many side passages become separate caves, like the Crystal Cave for example. Underground Cave Rivers & Streams - Cave rivers or streams, are active waterways. This means during rainy season (in summer), and hurricane season (in the fall), the cave can be completely fill with water. This is evidenced by large logs which are jammed into the roof of the cave ceiling. The cave stream also carries a great deal of sand and cobble-sized gravel. Some of this river gravel has its origin in the crystalline rocks of the central Maya Mountains. The main component of these river gravels is from chert or silica nodules that are part of the original limestone rock. These underground rivers behave much like surface ground rivers. Which means these river channels have a meander system similar to a surface river. Meandering rivers can change their course, and create what are known as high water levels, or abandoned meanders. As the limestone dissolves, it is redeposited in the caves as flowstone and dripstone. These caves then become full of stalagmites, stalactites, and other types of cave formations. The formations that are near to the water level are often redissolved during the higher water levels. This is a reminder that caves have a life of their own. Caves can be youthful, they grow old, and finally they die, as they are eroded away. The Chiquibul Cave System is an excellent example of a mature Karst landscape, and the site reminds us that nothing, in geology or life, is forever. Help us to protect this awesome natural wonder. Examples of Karst Topography NOHOCH CHEN SINKHOLE EXPEDITION Nohoch Ch'en Sinkhole Expedition In early 2015, a team of 22 people set out to reach the Chiquibul National Forest in Belize, to discover and explore the Nohoch Chen Sinkhole. A massive bowl with sheer limestone walls, dropping 500 feet below the jungle, and brethtaking views. Nohech Ch'en Sinkhole Expedition (as told by Marguerite Bevis (Jim's Wife) The seeds for the Nohoch Ch’en Expedition were planted years ago when Neil Rogers flew over the Chiquibul Forest and took the first images we had ever seen of the giant sinkhole. Jim Bevis (owner and operator of Mountain Equestrian Trails), in Cayo kept this photo over his desk for some twenty odd years. This was one expedition he was determined to make happen. In time, Jim approached Mr. Rafael Manzanero, Executive Director of Friends for Conservation & Development (FCD), for endorsement and to ensure that an expedition into this massive sinkhole would be beneficial to the development of the FCD Karst Management Program in this remote area of the Chiquibul. The answer was, “Let’s do it.” The purpose of the expedition would be to document one of the most remote, rugged and unexplored locations in Belize and to hopefully further justify to Belize and the world, the uniqueness and value of this region as a potential World Heritage site. The Nohoch Ch’en sinkhole, the largest of 49 collapsed doline formations that are located mostly over the Chiquibul Cave System, is located in an area where surface water is very scarce, making it challenging to explore for long periods of time. Very little scientific information was available for this region of the Chiquibul National Park, let alone the forest environment at the bottom of the 650’ wide and 450’ deep sinkhole. In the year 2000, several members of the Millennium Expedition descended by rope into the sinkhole and made brief observations, but time did not permit exploration and little data was collected, as this was not the main focus of their expedition. Jim spent months studying maps, making lists, planning every detail. He assembled a seasoned exploration team for the project: Jim Bevis, expedition leader, Marguerite Bevis (myself), camp nurse and communications coordinator, and our son, Arran Bevis, area exploration leader, have all led and outfitted expeditions into the Chiquibul since the early 90’s. Jim Allan, a world-class alpine climber and explorer, instructed and supervised the difficult technical climbs required. Neil Rogers is an adventure travel specialist who took the photo that inspired us all. Tony Rath, photographer extraordinaire, who’s well known images have attracted worldwide attention to the beautiful Jewel that is Belize, offered major support during the planning and implementation phase. Therese Rath, Tony’s lovely, vivacious, and energetic wife, was invited along to assist Tony and to cook, which she did amazingly. Bruce Holst, of The Marie Selby Botanical Gardens is perhaps the world’s top specialist in epiphytes and other tropical forest plant species. He has been doing research in Belize for over 20 years and has collected and catalogued over 10,000 species of different flora here. Bruce’s assistant, Ella Baron, founder of the Caves Branch Botanical Gardens, also became a part of the team. They would spend all day finding and mapping new specimens, and then work for hours in the evenings sorting, identifying and pressing, plus saving live specimens for various botanical gardens, including the National Herbarium in Belize. Other team members included Giovanni Martinez, level 3 rope rigger and natural history expert, as the rescue technician and lead medic; Nickolas Lormand, a film student from New Mexico; Joey Martinez, camp cook and “chain-saw Ninja”, when it came to clear the old logging road for the expedition to navigate deep in the Chiquibul; Hugo Orellano, camp cook and maintenance man; and Jairo ViaFranco, the “bush”mechanic who was able to fix anything and saved the day on several occasions. The FCD Rangers were essential team members. Gliss Penados and Boris Arevalo contributed significantly to the scientific component of the expedition gathering data and mapping areas by GPS. There were other FCD Rangers whose vigilance and knowledge of the area, made for a safe working and living environment. These are the brave sentinels of the Chiquibul. They kept guard day and night and reported their observations of the presence of potential intruders. Their dedication and commitment to conserving the Chiquibul is inspiring. Having loaded two trailers, one with supplies, the other with passengers, twenty team members began the journey on January 26, 2015 into the deepest parts of the Chiquibul Forest Reserve. We drove the tractors/trailers to FCD’s Tapir Camp where we spent the first night. We travelled the good road almost to Millonario but at that point, we had to reopen an old logging road for about ten kilometers to the base camp location at the pass below Nohoch Ch’en. Reopening the road took three days. On the fourth day, after hours of backbreaking labor, just before dark, we set camp at our final destination. MET donated a Weatherhaven 20’x20’shelter to FCD. This was an opportunity to instruct the FCD Rangers to set it up for use as a base camp facility. The tent housed a charging station for everyone’s electronics and was powered by a small generator for a few hours a day to charge the 12 volt batteries for continued use after the generator was turned off. A large table was in the center for food preparation and serving. Along the edges of this tent was storage for food and equipment. A water station was constructed to filter the dark tea-colored water brought from a Maya aguada every other day by tractor. After filtration the water was still slightly colored but purification drops were added for additional protection and nobody became ill. On the first morning at the base camp, the scientists and photographers went to the top of the sinkhole for the first glimpse and images of this magnificent natural wonder. Others stayed in camp to set up the large shelter and a kitchen and build sanitary facilities. Thus began the daily routine of exploration and discovery. While some descended into the sinkhole by bosun’s chair, others continued to search for a source of water closer to camp and for an above ground entrance to the giant underground chambers of the Chiquibul Cave. The scientists were constantly at work searching for epiphytes, and they were excited by what they found. Dr. Holst found over 50 species of orchids alone. Specimens have been sent to Marie Selby Gardens. At the bottom they discovered large boulders covered with mosses, ferns, and orchids, and a profusion of epiphytes. Getting to the bottom of the sinkhole was not easy. A Harken winch helped to lower people down to a ledge about a third of the way down into the hole and then they could carefully make their way to the bottom. Each member was carefully harnessed and double checked for safety before descending or ascending. Team members discovered small shallow holes in the vertical walls all around the sinkhole. One small cavern could be seen from across the rim and at the entrance were large Mayan pots. Climbers spent a day and a half accessing this cave, to photograph the three large storage urns. What we know for sure is that the bottom of the sinkhole had not been explored or looted by modern man and it is extremely rich with various plants and epiphytes. Bruce Holst called the sinkhole and its rim, “exceptionally rich beyond words.”The only mammals seen in the sinkhole were Spider Monkeys that climbed effortlessly in and out of the sinkhole via cascading vines. A pair of Orange-Breasted Falcons were seen every day and are likely nesting in the sinkhole cliffs, but no nest was seen. Slate-colored Solitaires could be heard singing their incomparable flute-like song most days. There also appears to be Mayan ceremonial temples on the west and east rims of the sinkhole and temples with plazas were found for miles in every direction near the sinkhole hill. Ancient Mayan agricultural terraces were everywhere. It became evident that the Maya did climb down into the sinkhole to build ceremonial places to leave pottery or mementos, presumably to honor the dead. It is unlikely anyone lived there. There is no water in the bottom of the hole; however, possibly it was there in the day of the Maya. Nohoch Ch’en means great well and water was a precious resource then and now. There was an aguada at the base of a Maya site near our base camp, which still holds water today. There was very little water elsewhere – a few muddy puddles but no creeks, no rivers. Water is the major limiting factor in planning this and future expeditions. Also evident during the expedition, is that the area is heavily trafficked by intruders. There was a lot of Guatemalan branded trash around their campsites and trails. They are not taking just Xate; they are taking valuable hardwoods and wildlife and leaving behind garbage. The area is at risk of becoming one big Guatemalan milpa. The issues are complex and there is no simple answer. In order to protect the Chiquibul, FCD requires the finances to sustain the efforts on the ground. Concerned citizens at home and abroad can help by supporting FCD. To know more on how to help visit the www.fcdbelize.org website. The Chiquibul Forest is rich in biodiversity. The bottom of the sinkhole is a virtual time capsule of plant specimens and undisturbed Mayan relics. Mayan terraces and buildings abound. Consider that also within the Chiquibul Forest is the natural bridge, “Puente Natural” and the Chiquibul Cave System, the largest cave system in Central America, not to mention the Mayan city of Caracol. The Upper Macal and Raspaculo Rivers are nesting grounds for the endangered Scarlet Macaw and have an abundance of wildlife. Let’s not forget that these are the headwaters for the Belize River, possibly your drinking water. The Chiquibul Forest is important not only for Belizeans but for the world. It is our unique and irreplaceable natural and cultural heritage. Photo Credits: by Tony Rath and Neil Rogers

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Is located on the island of Ambergris Caye, directly across from the Belize Barrier Reef, off the mainland coast of Belize. The property is nestled in a cluster of Australian Pine trees, backed to a littoral jungle, and surrounded by tropical gardens. It's about a one minute walk from the property to the beach, and a 10-15 minute drive from the island airstrip to the property.

We offer one bedroom suites (455 s.f.) of living area to include: livingroom, kitchenette, private bathroom and bedroom. We are also about a one minute walk from one of the best restaurants on the island serving (breakfast, lunch & dinner). Within walking distance you can find: (3) blocks is Robyn's BBQ (4) blocks is 2 fruit stands (5) blocks local grocery store IF YOU'RE COMING TO BELIZE TO............... If you're coming to Belize to dive the Blue Hole, descend the shelf walls at Turneffe, snorkel the Barrier Reef, explore Mayan ruins, rappel into a cave, kayak along the river through caves, zip line through jungle tree tops, hike through a cave to see an ancient human skeleton, swim with sharks, listen to Howler Monkey's, hold a boa constrictor, feed a jaguar, horseback ride through the jungle, canoe through a cave, rappel down a waterfall, sail around an island, enjoy cocktails & dinner to a sunset, climb 130' feet to the top of a Mayan ruin, rip up the jungle trails on an ATV, float through a series of caves on a tube, and sip on a rum punch..... then this is the place for you. Belize Budget Suites, offers you clean, affordable, attractive, accommodations, at prices that allow you to do all the things just mentioned. Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

For All Your Home Improvement Needs

For all Your Real Estate Needs

501-226-4400 10 Coconut Dr. San Pedro, Belize Your Ad Could Go Here

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed