Over 40% of Belize has been dedicated to Natural Parks or Reserves by the Belize Government. Making Belize the Top Travel Destination in the World, for seeing Animal & Marine Wildlife.

535,235 + Acres Protected

Taking Protective Measures To Protect It's Natural Treasures

THE BELIZE GOVERNMENT

Between 1990 and 1992, some 535,235+ acres were put under permanent protection by Belize, including more than 200,000 acres of tropical forest in the Chiquibul region; 6,000 acres of mangrove wetlands in the Burdon Canal zone; and 97,000 acres of critical watershed in the Bladen Nature Reserve. During that same period, the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary (the world's only jaguar refuge) was expanded from 3,600 to 102,000 acres. Since then, Belize has added more parks and reserves, including designation of the entire 75-square mile Glover's Reef Atoll as a marine reserve and of the 23-square mile Bacalar Chico area as a combination marine reserve and national park.

Belize has shown remarkable leadership in protecting tropical forests and marine resources, and many Belizeans deserve credit for these positive actions. Now the government is shifting its attention from establishment of parks and protected areas to long-term, on the ground area management. In order to accomplish this, the country's natural resources need to pay for themselves.

Belize has shown remarkable leadership in protecting tropical forests and marine resources, and many Belizeans deserve credit for these positive actions. Now the government is shifting its attention from establishment of parks and protected areas to long-term, on the ground area management. In order to accomplish this, the country's natural resources need to pay for themselves.

Exploring the Belize Rainforest

In overlooking the endless sea of emerald green, it is nearly impossible to imagine that 1,200 years ago this whole region had been converted to agriculture and silviculture. Satelite mapping data have revealed the outlines of ancient farmers' fields and irrigation trenches proving that intensive use of the land had spared very little of the original forest. According to plant biologist C.F. Cook, "Truly virgin forests seem not to exist in Central America. Relics of ancient agricultural occupation seem now where to be lacking even in regions now entirely uninhabited, in dense forests as well as in open desert regions." Botanists believe that the present composition of the forest at TIkal is largely due to Mayan silviculture. By the time conquistador Herman Cortez visited the area, in 1525, the rain forest had already grown back and looked very similar to how it looks today. Nature is very resilient and, given the chance, forests can return to areas once degraded by unwise human development.

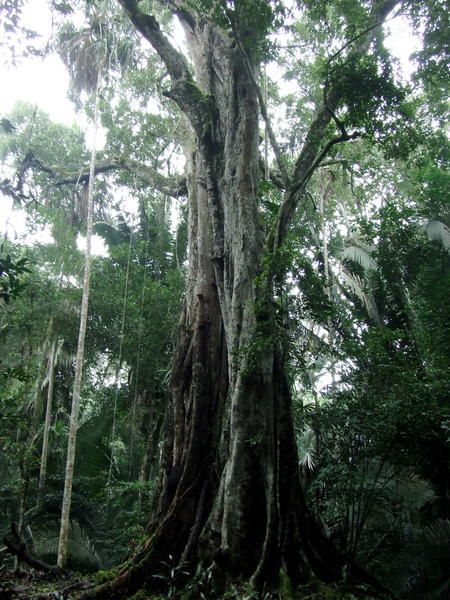

Technically speaking, the forest found in the northern half of Guatemala's Peten Province is referred to as Tropical Moist Forest, differing somewhat from true rain forest due to the existence of marked wet and dry seasons. The limestone plains of Peten include a vast region with abundant examples of both arid and tropical flora. Much of the plant life is identical to that of the Yucatan Peninsula and includes many endemic species. Broad-leave forests of mahogany, yellow taberbuia, cedar, sapodilla (from which the chicle base for chewing gum is made), and giant buttressed ceibas compete with strangler figs and are covered in a profusion of huge philodendrons, orchids, lianas, monsteras, and bromeliads. Lakes, wooded swamps, undrained sinkhole ponds, or aguadas, and stretches of grassland and savannah are scattered throughout the forest. Since very little sun can reach the forest floor there are a few flowers. The trees are tall and straight reaching fity meters up to the forest canopy. Trunks are covered with lichens and mosses which make them very difficult to identify. The sounds are those of little birds singing, flocks of screeching parrots, the buzzing and chirping of insects and occasionally the distant roar of a howler monkey, sounding more like a tiger than a medium sized primate.

As you walk along the main pathways of the park there is a good chance that you will see ocellated turkeys, coatimundis, grey fox, brocket and white-tailed deer, spider and howler monkeys, woodpeckers, trogons, and many other species. There are also numerous nature trails which branch off from the main paths which take you into the deep jungle. Because these smaller trails are not well marked it is recommended to obtain a guide. Off-duty park guards are usually available to provide this service and their abundant knowledge about forest life makes them a definite asset for those new to tropical ecosystems.

In closing, please do not attempt to venture into rain forest jungle areas alone. If you are unfamiliar with various trails, please seek the assistance of an experienced guide. Always tell somewhere where you are headed before you leave, and when you are expected to return. Make sure you are dressed appropriately. We recommend long sleeve (light weight) shirts, long (light weight) pans, socks and good hiking books with covered toe and ankle protection. Carry a cell phone with you, ample bug repellent, snacks, and ample water for your adventure.

Technically speaking, the forest found in the northern half of Guatemala's Peten Province is referred to as Tropical Moist Forest, differing somewhat from true rain forest due to the existence of marked wet and dry seasons. The limestone plains of Peten include a vast region with abundant examples of both arid and tropical flora. Much of the plant life is identical to that of the Yucatan Peninsula and includes many endemic species. Broad-leave forests of mahogany, yellow taberbuia, cedar, sapodilla (from which the chicle base for chewing gum is made), and giant buttressed ceibas compete with strangler figs and are covered in a profusion of huge philodendrons, orchids, lianas, monsteras, and bromeliads. Lakes, wooded swamps, undrained sinkhole ponds, or aguadas, and stretches of grassland and savannah are scattered throughout the forest. Since very little sun can reach the forest floor there are a few flowers. The trees are tall and straight reaching fity meters up to the forest canopy. Trunks are covered with lichens and mosses which make them very difficult to identify. The sounds are those of little birds singing, flocks of screeching parrots, the buzzing and chirping of insects and occasionally the distant roar of a howler monkey, sounding more like a tiger than a medium sized primate.

As you walk along the main pathways of the park there is a good chance that you will see ocellated turkeys, coatimundis, grey fox, brocket and white-tailed deer, spider and howler monkeys, woodpeckers, trogons, and many other species. There are also numerous nature trails which branch off from the main paths which take you into the deep jungle. Because these smaller trails are not well marked it is recommended to obtain a guide. Off-duty park guards are usually available to provide this service and their abundant knowledge about forest life makes them a definite asset for those new to tropical ecosystems.

In closing, please do not attempt to venture into rain forest jungle areas alone. If you are unfamiliar with various trails, please seek the assistance of an experienced guide. Always tell somewhere where you are headed before you leave, and when you are expected to return. Make sure you are dressed appropriately. We recommend long sleeve (light weight) shirts, long (light weight) pans, socks and good hiking books with covered toe and ankle protection. Carry a cell phone with you, ample bug repellent, snacks, and ample water for your adventure.

Jungle Etiquette

Safety & Health Tips

While most tours are safe, there are risks involved in any adventurous activity. Know and respect your own physical limits before undertaking any strenuous activity. be prepared for extremes in temperature and rainfall and for wide fluctuations in weather. a sunny morning hike can quickly become a cold and wet ordeal, so it's usually a good idea to carry along some form of rain gear when hiking in the rainforest, or to have a dry change of clothing waiting at the end of the trail. Make sure to bring along plenty of sunscreen when you're not going to be covered by the forest canopy.

If you do any back country packing or camping, remember that it really is a jungle out there. Don't go poking under rocks or fallen branches. Snakebites are very rare, but don't do anything to increase the odds. If you do encounter a snake, stay calm, don't make any sudden movements, and do not try to handle it. Also, avoid swimming in major rivers unless a guide or local operator can vouch for their safety. Though white-water sections and stretches in mountainous areas are generally pretty safe, most mangrove canals and river mouths in Belize support healthy crocodile and caiman populations.

Bugs and bug bites will probably be your greatest health concern in Belize, and even they aren't a big a problem as you might expect. Mostly bugs are an inconvenience, although mosquitoes can carry malaria or dengue. A strong repellent and proper clothing will minimize both the danger and inconvenience; you may also want to bring along some cortisone or Benadryl cream to soothe itching. At the beaches, you'll probably be bitten by sand fleas, or "no-see-ems." These nearly invisible insects leave an irritating welt. Try not to scratch, as this can lead to open sores and infections. no-see-ems are most active at sunrise and sunset, so you might want to cover up or avoid the beaches at these times.

And remember.............whenever you enter and enjoy nature, you should tread lightly and try not to disturb the natural environment. There's a popular slogan well known to most campers that certainly applies here: "Leave nothing, but footprints, take nothing but memories." If you must take home a souvenir, take photos. Do not cut or uproot plants or flowers. Pack out everything you pack in, and please do not litter.

If you do any back country packing or camping, remember that it really is a jungle out there. Don't go poking under rocks or fallen branches. Snakebites are very rare, but don't do anything to increase the odds. If you do encounter a snake, stay calm, don't make any sudden movements, and do not try to handle it. Also, avoid swimming in major rivers unless a guide or local operator can vouch for their safety. Though white-water sections and stretches in mountainous areas are generally pretty safe, most mangrove canals and river mouths in Belize support healthy crocodile and caiman populations.

Bugs and bug bites will probably be your greatest health concern in Belize, and even they aren't a big a problem as you might expect. Mostly bugs are an inconvenience, although mosquitoes can carry malaria or dengue. A strong repellent and proper clothing will minimize both the danger and inconvenience; you may also want to bring along some cortisone or Benadryl cream to soothe itching. At the beaches, you'll probably be bitten by sand fleas, or "no-see-ems." These nearly invisible insects leave an irritating welt. Try not to scratch, as this can lead to open sores and infections. no-see-ems are most active at sunrise and sunset, so you might want to cover up or avoid the beaches at these times.

And remember.............whenever you enter and enjoy nature, you should tread lightly and try not to disturb the natural environment. There's a popular slogan well known to most campers that certainly applies here: "Leave nothing, but footprints, take nothing but memories." If you must take home a souvenir, take photos. Do not cut or uproot plants or flowers. Pack out everything you pack in, and please do not litter.

What is an Eco-System?

What is an Ecosystem?

An ecosystem may be defined as a self-sustaining and self-regulating natural community of organisms (i.e. living things) interacting with one another and their environment. A community consists of populations of plants and animals living in a given area at a given time. An organism's environment consists of biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) things. From its environment, a living thing-plant, animal, fungus or microbe-derives the conditions that enable it to survive, including food (energy), water, living space, sunlight and a multitude of other essentials. There are even in-built biological controls that prohibit overpopulation, such as grazers and browsers for plants, and predators for animals, in addition to parasites, diseases, and others. A health ecosystem is one in which all of the organisms are in balance with one another.

What is Eco-Tourism?

Nature-based tourism - often referred to as "eco-tourism" - is strongly and officially encouraged in Belize. Politicians and bureaucrats are hopeful that Belize can learn from the mistakes of others, weighing the advantages of badly needed foreign income against the irreversible damage that unbounded traditional tourism and agriculture can inflict. But just as "it takes a village" to raise a child, it takes an entire country to carefully preserve and wisely manage natural resources. Hotels, tour operators, trade organizations, educators, individuals, and entrepreneurs throughout Belize have responded to the call for enlightened action.

The Belize Eco Tourism Association (BETA) was formed in 1993 by a few members of the Belize Tourism Industry Association as a conservation-oriented branch of that trade group. BETA's mission is to promote environmentally responsible tourism, to be sensitive to the impacts of tourism, to promote education for locals and visitors, and to promote such concerns as pollution prevention.

An ecosystem may be defined as a self-sustaining and self-regulating natural community of organisms (i.e. living things) interacting with one another and their environment. A community consists of populations of plants and animals living in a given area at a given time. An organism's environment consists of biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) things. From its environment, a living thing-plant, animal, fungus or microbe-derives the conditions that enable it to survive, including food (energy), water, living space, sunlight and a multitude of other essentials. There are even in-built biological controls that prohibit overpopulation, such as grazers and browsers for plants, and predators for animals, in addition to parasites, diseases, and others. A health ecosystem is one in which all of the organisms are in balance with one another.

What is Eco-Tourism?

Nature-based tourism - often referred to as "eco-tourism" - is strongly and officially encouraged in Belize. Politicians and bureaucrats are hopeful that Belize can learn from the mistakes of others, weighing the advantages of badly needed foreign income against the irreversible damage that unbounded traditional tourism and agriculture can inflict. But just as "it takes a village" to raise a child, it takes an entire country to carefully preserve and wisely manage natural resources. Hotels, tour operators, trade organizations, educators, individuals, and entrepreneurs throughout Belize have responded to the call for enlightened action.

The Belize Eco Tourism Association (BETA) was formed in 1993 by a few members of the Belize Tourism Industry Association as a conservation-oriented branch of that trade group. BETA's mission is to promote environmentally responsible tourism, to be sensitive to the impacts of tourism, to promote education for locals and visitors, and to promote such concerns as pollution prevention.

Saving Tropical Habitats

This is a sensitive subject for me, as I love animals and anything that has to do with them.

Environmentalists are well aware of what can - and often does - occur when travel in the tropics is promoted with little regard for natural resources: protective mangrove trees are stripped by builders from sandy shorelines; fragile coral reefs are damaged by inquisitive but uniformed divers and snorkelers; commercial marine species, such as conch and lobster, are depleted to meet restaurant demands; indiscriminate poaching may decimate wildlife populations; and oblivious amateur cavers may degrade speleothems formed over thousands of years. Despite its own best efforts, Belize has not escaped this long list of injuries. Yet many individuals, in government, academia, and private industry, are making a determined effort to provide effective conservation education to each and every visitor.

Perhaps the part of the country facing the most intense development pressure is the marine environment, particularly the coral reef formations immediately surrounding the most-visited cayes, Ambergris Caye and Caye Caulker. Coral reefs are the marine equivalents of tropical rain forests.

"In most coral species, each individual polyp lays down a skeletal container of calcium carbonate that surrounds and protects its soft body," biologist Edward O. Wilson wrote in The Diversity of Life. "Coral colonies grown by the budding of individual polyps, with the skeletal cups being added one on another in a set geometric pattern particular to each species. The result is a lovely, bewildering array of skeletal forms that mass together to make the whole reef - a tangled field of horn corals, brain corals, staghorn corals, organ pipes, sea fans, and sea whips." Some formations are thousands of years old.

Belize's barrier reef suffers injury every time a boat anchor is randomly cast and hauled in or a diver bumps against a piece of living coral. When these centuries-old-marine architects are touched, they often begin to turn black and die. Unfortunately, many collectors cannot seem to resist the urge to (illegally) collect sea fans, black coral, and even aquarium-bound fish. Commercial fishing throws the food chain out of balance when desired species are removed en masse. Important breeding and feeding grounds for lobster, conch, turtles, grouper, and waterfowl are destroyed by unrestricted fishing or when mangrove and sea grass beds are removed (often illegally) by developers. Over the long run, no one knows what the cumulative effort of all these changes will be.

Environmentalists are well aware of what can - and often does - occur when travel in the tropics is promoted with little regard for natural resources: protective mangrove trees are stripped by builders from sandy shorelines; fragile coral reefs are damaged by inquisitive but uniformed divers and snorkelers; commercial marine species, such as conch and lobster, are depleted to meet restaurant demands; indiscriminate poaching may decimate wildlife populations; and oblivious amateur cavers may degrade speleothems formed over thousands of years. Despite its own best efforts, Belize has not escaped this long list of injuries. Yet many individuals, in government, academia, and private industry, are making a determined effort to provide effective conservation education to each and every visitor.

Perhaps the part of the country facing the most intense development pressure is the marine environment, particularly the coral reef formations immediately surrounding the most-visited cayes, Ambergris Caye and Caye Caulker. Coral reefs are the marine equivalents of tropical rain forests.

"In most coral species, each individual polyp lays down a skeletal container of calcium carbonate that surrounds and protects its soft body," biologist Edward O. Wilson wrote in The Diversity of Life. "Coral colonies grown by the budding of individual polyps, with the skeletal cups being added one on another in a set geometric pattern particular to each species. The result is a lovely, bewildering array of skeletal forms that mass together to make the whole reef - a tangled field of horn corals, brain corals, staghorn corals, organ pipes, sea fans, and sea whips." Some formations are thousands of years old.

Belize's barrier reef suffers injury every time a boat anchor is randomly cast and hauled in or a diver bumps against a piece of living coral. When these centuries-old-marine architects are touched, they often begin to turn black and die. Unfortunately, many collectors cannot seem to resist the urge to (illegally) collect sea fans, black coral, and even aquarium-bound fish. Commercial fishing throws the food chain out of balance when desired species are removed en masse. Important breeding and feeding grounds for lobster, conch, turtles, grouper, and waterfowl are destroyed by unrestricted fishing or when mangrove and sea grass beds are removed (often illegally) by developers. Over the long run, no one knows what the cumulative effort of all these changes will be.

Searching for Wildlife

Animals in the forests are predominately nocturnal. When they are active in the daytime, they are usually elusive and on the watch for predators. Birds are easier to spot in clearings or secondary forest than they are in primary forests. Unless you have lots of experience in the tropics, your best hope for enjoying a walk through the jungle lies in employing a trained and knowledgeable guide. (By the way, if it's been raining alot and the trails are muddy, a good pair of rubber boots comes in handy. These are usually provided by the various lodges or at the sites, where necessary.)

Here are a few helpful hints:

1. Listen. Pay attention to rustling leaves; whether it's monkeys above or pizotes on the ground, you're most likely to hear an animal before seeing one.

2. Keep quiet. Noise will scare off animals and prevent you from hearing their movements and calls.

3. Soften your focus and allow your peripheral vision to take over. This will allow you can catch glimpses of motion and then focus in on the animal.

4. Bring binoculars & practice using them before you come. Don't miss something wonderful because you don't know how to use your binoculars.

5. Dress appropriately. You can't focus on your binoculars, if you're busy swatting mosquitoes.

6. Dress light, long pants, long-sleeved shirts are your best bet. Comfortable hiking boots are a real bonus, except where heavy rubber boots are necessary.

7. Don't wear loud bright colors; the better you blend in with your surroundings, You'll have a better chance of spotting wildlife.

8. Be patient. The jungle isn't on a schedule. however, your best shots at seeing forest fauna are in the very early-morning and late -afternoon hours.

7. Read up. Familiarize yourself with what you're most likely to see.

A book we recommend is to have a copy of "Bird of Belize" by H. Lee Jones, and other wildlife field guides. Another good all-around book to have is Les Beletsky's Belize and Norther Guatemala: "The Eco-travellers' Wildlife Guide."

Here are a few helpful hints:

1. Listen. Pay attention to rustling leaves; whether it's monkeys above or pizotes on the ground, you're most likely to hear an animal before seeing one.

2. Keep quiet. Noise will scare off animals and prevent you from hearing their movements and calls.

3. Soften your focus and allow your peripheral vision to take over. This will allow you can catch glimpses of motion and then focus in on the animal.

4. Bring binoculars & practice using them before you come. Don't miss something wonderful because you don't know how to use your binoculars.

5. Dress appropriately. You can't focus on your binoculars, if you're busy swatting mosquitoes.

6. Dress light, long pants, long-sleeved shirts are your best bet. Comfortable hiking boots are a real bonus, except where heavy rubber boots are necessary.

7. Don't wear loud bright colors; the better you blend in with your surroundings, You'll have a better chance of spotting wildlife.

8. Be patient. The jungle isn't on a schedule. however, your best shots at seeing forest fauna are in the very early-morning and late -afternoon hours.

7. Read up. Familiarize yourself with what you're most likely to see.

A book we recommend is to have a copy of "Bird of Belize" by H. Lee Jones, and other wildlife field guides. Another good all-around book to have is Les Beletsky's Belize and Norther Guatemala: "The Eco-travellers' Wildlife Guide."

Conservation Solutions

As one of the world's most environmentally aware countries, Belize has already set a standard of behavior that speaks for itself in big and small ways. The Belize Eco Tourism Association, for instance, has successfully implemented several projects that appear to have increased environmental awareness. They have done this by establishing communities such as: The Community Baboon Sanctuary, the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary, the Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary, the Shipstern Nature Reserve, and the Rio Bravo Conservation Area. These are just five of the many innovative example of how the demands of conservation can be successfully balanced with the fundamental economic needs of local people.

An innovative project in the southern part of the country demonstrates such sensitivity in action. In the largely undeveloped Toledo District, Maya villagers have opened thatch-roof guest houses for travelers. Others have opened their simple homes to visitors who want a firsthand look at a subsistence farming culture that has persisted for centuries.

Similar community-level approaches are proving to be key models for long-term protection of Belize's forests. The Friends of Five Blues, for example, was formed to manage the spectacular Five Blues Lake National Park, with its 200-foot deep inland lake surrounded by some 4,200 acres of lush, broadleaf tropical forest, interwoven with an other worldy labyrinth of limestone caves. The Friends of Five Blues complementary goal is to ensure that the local community directs natural history tourism and that the people living nearby realize financial rewards from tourism related enterprises.

An innovative project in the southern part of the country demonstrates such sensitivity in action. In the largely undeveloped Toledo District, Maya villagers have opened thatch-roof guest houses for travelers. Others have opened their simple homes to visitors who want a firsthand look at a subsistence farming culture that has persisted for centuries.

Similar community-level approaches are proving to be key models for long-term protection of Belize's forests. The Friends of Five Blues, for example, was formed to manage the spectacular Five Blues Lake National Park, with its 200-foot deep inland lake surrounded by some 4,200 acres of lush, broadleaf tropical forest, interwoven with an other worldy labyrinth of limestone caves. The Friends of Five Blues complementary goal is to ensure that the local community directs natural history tourism and that the people living nearby realize financial rewards from tourism related enterprises.