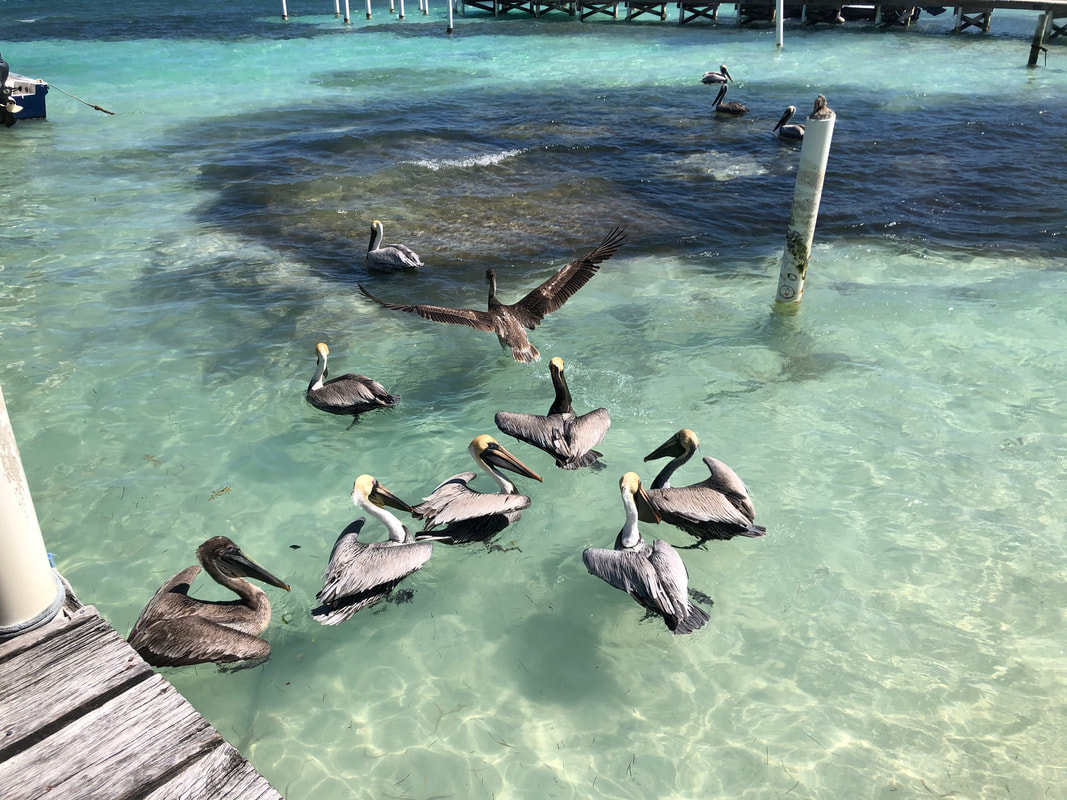

Pelicans in Belize

Of the six species of pelicans found throughout the world, the brown pelican is the most common in Belize. This species is characterized by webbed feet, a dark body, a gold neck with a silver stripe, and a wingspan that can reach up to 6-feet. Their throat pouch is very thin and can hold up to three times more food than their stomach. This comes in handy when this skilled predator hunts for food. By diving from heights of up to 60 feet, a pelican plunges into the water headfirst and comes to the surface with its bill full of fish. Using a technique of tilting its head back, all the water is drained out of the pouch and it swallows its prey, almost always fish and small crustaceans, whole.

Pelicans are one of Jaymin's favorite birds. He loves going to the ocean, to watch & feed them.

What is the Difference Between a White Pelican & Brown Pelican?

- One of the obvious difference is color

- White Pelicans (wingspan 108"|16.2 lbs.) are larger than Brown Pelicans (wingspan 79"|8.2 lbs.)

- White Pelicans the upper mandible is yellow to pinkish, with a yellow pouch.

- Brown Pelicans upper mandible is gray/brown with orange and green hints near the tip of the beck.

- White Pelican legs and feet are yellow.

- Brown Pelican legs and feet are gray to black.

White Pelicans

White Pelican Facts

|

Brown Pelicans

Brown Pelican Facts

|

Pelicans in General

Pelicans are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterised by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before swallowing. They have predominantly pale plumage, the exceptions being the brown and Peruvian pelicans. The bills, pouches, and bare facial skin of all species become brightly coloured before the breeding season. The eight living pelican species have a patchy global distribution, ranging latitudinally from the tropics to the temperate zone, though they are absent from interior South America and from polar regions and the open ocean.

Long thought to be related to frigatebirds, cormorants, tropicbirds, and gannets and boobies, pelicans instead are now known to be most closely related to the shoebill and hamerkop, and are placed in the order Pelecaniformes. Ibises, spoonbills, herons, and bitterns have been classified in the same order. Fossil evidence of pelicans dates back at least 30 million years to the remains of a beak very similar to that of modern species recovered from Oligocene strata in France. They are thought to have evolved in the Old World and spread into the Americas; this is reflected in the relationships within the genus as the eight species divide into Old World and New World lineages.

Pelicans frequent inland and coastal waters, where they feed principally on fish, catching them at or near the water surface. They are gregarious birds, travelling in flocks, hunting cooperatively, and breeding colonially. Four white-plumaged species tend to nest on the ground, and four brown or grey-plumaged species nest mainly in trees. The relationship between pelicans and people has often been contentious. The birds have been persecuted because of their perceived competition with commercial and recreational fishing. Their populations have fallen through habitat destruction, disturbance, and environmental pollution, and three species are of conservation concern. They also have a long history of cultural significance in mythology, and in Christian and heraldic iconography.

Long thought to be related to frigatebirds, cormorants, tropicbirds, and gannets and boobies, pelicans instead are now known to be most closely related to the shoebill and hamerkop, and are placed in the order Pelecaniformes. Ibises, spoonbills, herons, and bitterns have been classified in the same order. Fossil evidence of pelicans dates back at least 30 million years to the remains of a beak very similar to that of modern species recovered from Oligocene strata in France. They are thought to have evolved in the Old World and spread into the Americas; this is reflected in the relationships within the genus as the eight species divide into Old World and New World lineages.

Pelicans frequent inland and coastal waters, where they feed principally on fish, catching them at or near the water surface. They are gregarious birds, travelling in flocks, hunting cooperatively, and breeding colonially. Four white-plumaged species tend to nest on the ground, and four brown or grey-plumaged species nest mainly in trees. The relationship between pelicans and people has often been contentious. The birds have been persecuted because of their perceived competition with commercial and recreational fishing. Their populations have fallen through habitat destruction, disturbance, and environmental pollution, and three species are of conservation concern. They also have a long history of cultural significance in mythology, and in Christian and heraldic iconography.

Pelican Behavior

These large, gregarious birds often travel and forage in large flocks, sometimes traveling long distances in V-formations. They soar gracefully on very broad, stable wings, high into the sky in and between thermals. On the ground they are ungainly, with an awkward, rolling, but surprisingly quick walk. Their webbed feet make for water-ski landings and strong swimming. They forage by swimming on the surface, dipping their bills to scoop up fish, then raising their bills to drain water and swallow their prey. They also forage cooperatively: groups of birds dip their bills and flap their wings to drive fish toward shore, corraling prey for highly efficient, synchronized, bill-dipping feasts. Pairs court in circling flights and in strutting, bowing, and jabbing displays at a chosen nest sites. Though females lay two eggs, only one chick per nest usually survives—one harasses or kills the other (a behavior known as siblicide). At 2 to 3 weeks old, chicks leave their nests and form into groups called crèches. Parents continue to forage for them, returning to the creche and searching out their young to feed them. Pelicans respond to threats by flying aggressively into a near-stall or, on land, adopting an upright posture and grunting. More severe threats from aerial predators provoke open-billed displays where the pelican lunges forward, jabbing with its enormous bill. Predators include foxes, coyotes, gulls, ravens, Great Horned Owls, and Bald Eagles.

What Do They Eat?

American White Pelicans eat mostly small fish that occur in shallow wetlands, such as minnows, carp, and suckers. Schooling fish smaller than one half their bill length predominate, though they will take sluggish bottom feeders, salamanders, tadpoles, and crayfish. They may also take deeper water fish like tui chub that spawn in the shallows. Because they are opportunistic, their diet changes with water levels and prey species abundance. In some areas of the Great Plains, salamanders and crayfish can predominate in the pelicans' diet. These birds can take game fish like cutthroat trout during spawning runs when locally available. Their prey is usually of little commercial value, although catfish aquaculture ponds in the Mississippi Delta have become an increasingly favored food source in recent years, especially during spring migrations.

Pelican Nesting

A pelican pair will choose a flat nest site on gravel, sand, or soil near other pelicans at the same stage of the breeding cycle. In Belize, they will nest amongst sparse vegetation. Both sexes use their bills to rake up surrounding gravel, sand, or soil to create a shallow depression roughly 2 feet across with a rim usually no more than 8 inches high. Occasionally they dig into the bottom of the site as well and may include nearby vegetation, though neither of the pair leaves the site to gather material. Because of trampling, by the end of the nesting season, the broad cup is usually 2 inches deep at most.

Nesting Facts

Egg Length: 3.3-3.7 in (8.3-9.5 cm)

Egg Width: 2.0-2.2 in (5.2-5.5 cm)

Nestling Period: 63-70 days

Egg Description: Uniform chalky white, rough to the touch, becoming smooth and discolored over time.

Condition at Hatching: Naked and helpless, with an orange body and grayish white pouch and bill, unable to walk.

Nesting Facts

Egg Length: 3.3-3.7 in (8.3-9.5 cm)

Egg Width: 2.0-2.2 in (5.2-5.5 cm)

Nestling Period: 63-70 days

Egg Description: Uniform chalky white, rough to the touch, becoming smooth and discolored over time.

Condition at Hatching: Naked and helpless, with an orange body and grayish white pouch and bill, unable to walk.